When nuclear war came to Sheffield

Revisiting the horror and terrifying, ongoing relevance of apocalyptic BBC drama 'Threads' on its 40th anniversary

Thanks for joining me for this deep dive into Threads.If you’re new here, do check out this post for a bit more about me. TLDR: I'm a documentary filmmaker coming to the end of distributing my debut feature doc about the history of nuclear power and currently exploring/expanding into the next steps of my working adventures. If you enjoy my writing, do feel free to leave a comment. And I'd love it if you'd consider subscribing to get all my posts delivered straight to your inbox or the Substack app.

[CONTAINS SPOILERS]

'THE NIGHT THE COUNTRY DIDN'T SLEEP'

On the evening of Sunday 23rd September 1984, viewers tuning into BBC2 after a cosy evening watching Germaine Greer on a vintage paddle steamer, a profile of Bury St Edmunds and Championship Darts1, were in for a shock.

The BBC did offer this brief on-screen introduction from journalist John Tusa.

Frankly though, Tusa's understated warning that 'some of the scenes which follow may distress you' could scarcely have adequately prepared anyone watching for what's widely considered one of the most traumatising pieces of television ever broadcast, one that 40 years later has lost absolutely none of its bleak and unremitting horror.

Indeed, in many ways, the experience of watching it in 2024 is even more unsettling. But I'm getting ahead of myself...

For anyone not familiar with it, Threads is a feature-length docudrama that follows the ordinary residents of Sheffield, in Yorkshire, England, through the run-up to, and aftermath of, a nuclear exchange over Britain by the Cold War superpowers. The title comes from a brief opening sequence of a spider spinning a web, a metaphor for the 'threads' that make up the fabric of society, which comes with an ominous warning:

“But the connections that make society strong, also make it vulnerable.”

Fully the first three quarters of an hour of its 112 minute running time feels like an episode of a soap opera, or even a fly-on-the-wall documentary, so low key and naturalistic is its style.

We watch as two young lovers, Jimmy and Ruth, one working class, one middle class, deal with an unplanned pregnancy. We see the couple get engaged, talking about the future and decorating their new flat, while their respective families muddle along as they deal with the news, their younger siblings bickering, their parents worrying.

But all the while, in the background of this everyday human drama, there is the slow drumbeat of impending conflict. We get glimpses of the wider world in radio and TV news reports and newspaper headlines. There are mentions of a lost submarine and a Soviet attack in Iran. We see anti-nuclear demonstrators protesting in the streets and ill-prepared officials, staring at charts, worrying about fuel stocks and supply lines.

As hostilities escalate and a national emergency is declared, food supplies start to be affected, petrol stations are closed and families pack up their cars attempting to flee the city. None of it seems quite real to people and black humour punctuates the sense of growing dread:

“I tell you what, if the bomb does drop I want to be pissed out of my mind and straight underneath it when it happens.”

“If we are gonna kop it, we might as well go out with a bang”

And then it finally happens. At just after 8.30 in the morning, the first bomb explodes. The minutes that follow are visceral. People scream and run in abject terror; one woman memorably urinates herself. It's a scene of utter, apocalyptic pandemonium and chaos. And from this point on, the nightmare never gives up for a single moment.

More nuclear strikes take place. Charred limbs and dead pets pile up in the streets; people wander, blinded, disfigured and starving. Down in their bunker, local council officers, overwhelmed and panicked, argue in futile anger as they make unthinkable decisions about who to give food to and who is just going to die anyway. The local hospital is a vision of hell, doctors surrounded by dying and already-dead patients and carrying out amputations without anaesthetic.

In a shocking move that defies normal dramatic convention, one of the two main characters, Jimmy, simply disappears after the immediate impact and is never seen or heard of again in the rest of the film. This of course is what would, in reality, happen. Many thousands of people's loved ones would be obliterated in an instant.

Yet arguably Jimmy's (presumed swift) fate is better than Ruth's. She sees her family perish from radiation sickness; is forced to leave what remains of the city for a scorched and devastated countryside, where she find herself eating a dead, probably irradiated sheep, to ward off starvation; and she ends up giving birth by herself in a barn, forced to bite through the umbilical cord with her teeth.2

One might expect the birth of a baby to signal a small note of hope amongst the horror. But no such relief is offered here.

The film continues a relentless march on through the years following, showing us a nation reduced to medieval population levels in which civilisation has fundamentally broken down and even language is being lost – the adult survivors barely speak at all whilst the children growing up in this world speak a strange, degraded dialect with little more than the most basic utterances.

After Ruth dies, having gone blind from the effects of nuclear fallout, her daughter Jane is left to fend for herself, alone in this harsh, nihilistic world. The films ends, ten years on from the onset of nuclear war, in a moment of such unspeakable bleakness the screen cuts to black on the point of a scream rather than show it to us.

As the credits roll, it feels hard to breathe, to try to take in what we've seen. There's no crumb of a happy ending to take comfort in, no moment of catharsis, just complete and utter despair.

A REAL LIFE HORROR MOVIE - the facts behind Threads

The film is an extraordinary piece of work on every level. The writing and acting – including from hundreds of locals from Sheffield recruited as extras – is sparse, understated and incredibly affecting. And the visual impact of the film is truly remarkable, not least given that it was shot in only 17 days and on a modest public service broadcasting budget of just £400,000, about £1.3million in today's money.3

The visual effects we do see – the mushroom cloud, collapsing buildings and burning vehicles, melting milk bottles, horrific burn injuries – are chilling. But the sound design and expressions on people's faces speak to an even greater horror which our minds can hardly bear to conjure.

But for me, although all these aspects play a crucial role, they're not the real reason Threads is so frightening.

It's fiction, yes (thank God). But in a very meaningful way, it's also brutally, terrifyingly factual.

“As a teenager in Bingley library, they kept the VHS copy in a locked glass cabinet, alongside ELVIS - THE FINAL YEARS ( a book) which was for over-18s only!”

Directed by British science TV producer (and later Hollywood movie director) Mick Jackson, its dramatic rendering of the impacts of a nuclear strike is underpinned by unimpeachable, real-world facts and research.

Its immediate forerunner was a BBC science programme that Jackson had made a couple of years previously, which soberly runs through the specific effects of the blast impact, fireball and radiation release from a nuclear explosion on the human body and built environment, over an increasing radius from the bomb's detonation in central London.

For both that documentary and Threads itself, Jackson and writer Barry Hines, of Kes fame, did months of research, speaking to scientists, doctors and other experts, trawling through official Home Office reports and even spending a week at the UK's Civil Defence College, which provided training for “official survivors”.

One, at-the-time still new, scientific idea was particularly influential - that of nuclear winter. This concept was proposed by various scientists, including famed American cosmologist Carl Sagan, who extrapolated from knowledge of the atmospheric conditions on Mars and the observed impacts of volcanic eruptions on earth, to try to understand what might happen to the atmosphere in the event of nuclear war.

Their computer models suggested that the vast quantities of smoke that would be released into the upper atmosphere from the raging fires caused by the use of even a small fraction of the world's nuclear arsenal, would have catastrophic effects, not just in the areas where the strikes occurred, but across the globe.

As the soot from the smoke blocked out almost all of the sun's rays, the earth would endure weeks if not months of permanent twilight and temperatures would plunge, in many places to sub-zero levels. This would have devastating impacts on the global food system, leading to widespread crop failure and famine - as we see in Threads.

The faithful adherence to the best scientific and political predictions of what would actually happen in the event of nuclear war, was something Jackson viewed as essential to the project. It's the reason for the 'docu' portions of the docudrama – specifically Paul Vaughan's somber, dispassionate narration that's interwoven with the drama scenes all the way through the film.

Jackson has talked about how these narrated inserts caused a lot of friction with his writing collaborator Hines, who was deeply unconvinced of the merits of including them. In the end Jackson got his way – and at least for me, it was the right decision.

The baldly stated factual information – of megatons dropped, rising death tolls, social breakdown - serves as a continuing reminder, especially in the latter, bleakest parts of the film, that what we're watching isn't just a horror movie, a work of febrile imagination. It's based in fact. And all the harder to face for that.

“Our RE teacher made us watch Threads (age 13) and we still talk about it to this day. Talk about traumatising!”

'A WAY OF THINKING ABOUT THE UNTHINKABLE' - The Impact of Watching Threads

In a special interview to mark the 40th anniversary screening on the BBC, Jackson talks about the impact on viewers that night in 1984. He remembers the deafening silence from the telephone on the night of transmission – a stark contrast to the congratulatory phone calls from colleagues that would normally follow one of your programmes going out on TV.

Only the morning after was he told that very few people who'd watched it had gone to bed – they'd just sat in their chairs all night thinking about it, afraid perhaps of the nightmares that would come. It gave them, he said, a way of thinking about the unthinkable – the images from Threads lurking in their minds ready to resurface whenever they heard politicians glibly talking about actually using these weapons.

The film certainly left a very deep impression on me when I first watched it, about 15 years ago, one afternoon in my London flat, entirely unprepared for what was to come.

Rewatching it in 2024, whilst I clearly remembered the relentless spiral of bleakness, especially in the final section of the film, I realised I must have blanked out many of the specific physical and emotional horrors we see the characters endure, most notably the birth scene and the final image. These scenes in particular hit me all the harder this time around, now that I've got children of my own.

In writing this piece I also solicited other people's thoughts and memories of Threads. I've sprinkled a few of the briefer responses I received throughout, but wanted to include two longer comments here, one from

on Substack and the other from Ian Mclellan on X.From Wendy:

I missed Threads when it was first shown on TV in 1984, though I remember colleagues talking about how realistic and horrific it was. I finally got round to watching it a few years ago and was riveted. I grew up near Sheffield, and the author Barry Hines lived down the road, so the locations and voices were all really familiar, which I think made it all feel even more personal.

I watched it with a couple of friends, one of whom was a council communications officer at the time, and he said he could imagine the council response team having similar reactions now. There was that contrast between local bureaucracy in the council “bunker” and the apocalyptic scenes outside. The image of the family sheltering behind a propped door stuck with me. As if that would save them. Such a bleak drama, but so important and so well-made.

And from Ian:

I do have memories of watching Threads in 1984. It is intertwined in my head with other books and TV shows at the time like Z for Zachariah and Noah’s Castle. The world seemed very turbulent as a teenager and apocalypse seemed like a very real possibility.

3 years later and I was in the RAF and I got to see first hand what we were supposed to be training for. Looking back it was very Heath-Robinson and the scenes in Threads in the council bunker are true to life in my experience. On my second tour I was trained to be part of an NBC (nuclear biological chemical) Recce team. We would have been sent out to look for chemical weapon contamination. One of our pieces of ‘equipment’ was a broom handle to which we were supposed to attach a piece of ‘detector paper’. We would dab the ground and if the paper changed colour we would put up warning signs.

So Threads does a great job I think of mixing the horror and the bizarre. We all agreed at our radar site that we wouldn’t want to survive in to a nuclear winter. Threads had ‘educated’ us to the likely after effects of an attack.

Both of these responses I think reinforce just what an effective job Jackson and his team did on their research to make the events shown as true to life as they possibly could be. I can only imagine how much more difficult to watch the film must be when the locations are places familiar to you in your everyday life.

40 YEARS ON – Threads today

As a film made for TV rather than the cinema, and in spite of its tremendous psychological impact on viewers, Threads has still probably not been as widely seen as it deserves.

It was shown in the US, Canada and Australia (thanks

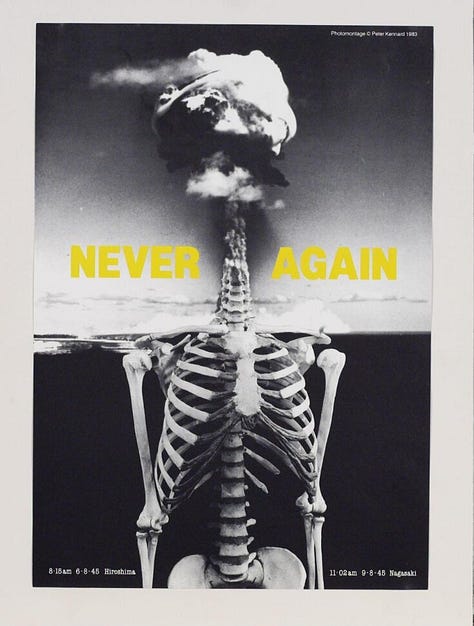

for confirming the last of these) a year after its UK broadcast, in 1985. The commercial channels that screened it took the highly unusual step of running it straight through without adverts. The BBC also repeated it in August 1985 to mark the 40th anniversary of the atomic bombs being dropped at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.It was then not shown again on British television for almost another two decades, until October 2003. Its recent 40th anniversary airing was thus only the fourth time the BBC had shown it. 4

From the reams of articles and online comments written to mark the anniversary it's clear how much the film still resonates. And it's not hard to see why.

Whilst some things have changed since 1984 – there are obviously no mobile phones and the casual sexism on display feels pretty jarring from today's vantage point – at the same time, many of the film's scariest aspects feel just as much a threat, if not even more so, now as they were four decades ago.

The first and most obvious consideration is the actual possibility of nuclear attack. The period in which Threads was made was undoubtedly a time of international instability. The arms race between the US and the Soviet Union intensified with the Soviet-Afghan war and the Americans' deployment of ballistic and cruise missiles in Western Europe. Mutual suspicion between the rival Cold War superpowers was front and centre of political and public consciousness.

And yet, by one credible estimate of the actual threat level – the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ Doomsday Clock initiative which has been in operation since 1947 – the chance of nuclear armageddon is higher now than it was in the mid-1980s.

In 1984, the Doomsday Clock was set at 3 minutes to midnight. Today it's 90 seconds to midnight, the closest to global catastrophe it has ever been. And earlier this year the UN Secretary General also warned the Security Council that the risk of nuclear warfare is at its highest level in decades.

The wars in Ukraine and Gaza, escalating conflict between Israel and Iran, the suspension of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, the commitment by both Russia and China to increase their nuclear weapons capabilities plus a new generation of nuclear warheads on the way here in Britain, not to mention North Korea and the possibility of Trump back in the White House – all of these things are contributing to a situation in which the use of a nuclear weapon feels like something that could plausibly happen.

And yet despite this record-breaking level of threat, our preparedness for the possibility of a nuclear strike, both literally and psychologically, seems notably lower than 40 years ago.

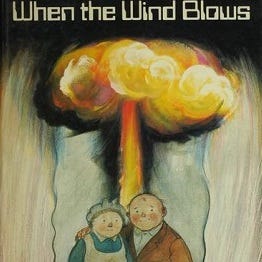

In the '80s, the sense that nuclear war might be just around the corner was widely felt. The topic was regularly discussed on news programmes, anti-nuclear activism was mainstream (helped by the coverage of the Greenham Common women's peace camps) and it was a touchstone of popular culture, across not just film and TV5, but pop music, art and literature.

You simply cannot say the same today. Where is this generation’s answer to Threads?

The closest we’ve come is probably last year’s blockbuster Oppenheimer biopic but that focuses far more of its attention on the psychodrama of the lead character’s personal moral choices than it does on the actual impacts of his work. We see nothing of the effect of the bomb tests on the indigenous population around the Los Alamos test site, never mind the effect on the Japanese victims of the two atomic bombs that were actually dropped. And of course it all feels like a period piece - tucked safely away from us across the decades of history.

“It’s so real and gritty and rather than feel dated given it's 40 years old, it feels even more documentary.”

And then there's the question of our official preparedness. Britain's Civil Defence Corps was disbanded in 1968 and a 2022 investigation by researchers at Warwick University found scant evidence of that the UK has made comprehensive plans to deal with a nuclear strike:

“We appear much less prepared than we were back in the 1960s when numerous preparations, including exercises in which the public participated, were made”.

Nuclear bunkers have taken on a kitsch, retro quality, like World War 2 Anderson shelters (see this recent article about a bunker in Norfolk that's up for sale). There's really no sense at all that the authorities would do a better job in the event of nuclear catastrophe than the overwhelmed bureaucrats we see in Threads.

In fact of course, we've very recently experienced just how hopelessly ill-prepared our government was when a major emergency hit – this despite boasting of our world class pandemic preparedness. It's almost unthinkable to imagine how our leaders would cope with a nuclear strike that they show no signs of thinking is possible, despite the current threat being at unprecedented levels.

And even if the threat were taken seriously, it's not at all clear that any government would have the capacity to adequately respond anyway, after 14 years of austerity and the withdrawal of state support from so many areas of public life.

The pre-armageddon scenes in Threads are a time capsule of Thatcherism, unsentimentally portraying the economic precarity that characterised life for so many in 1980s Britain. But the situation we find ourselves in today, with a 'black hole' in the public finances and millions in irregular, insecure work is scarcely better.

All in all, the experience of watching Threads today remains an incredibly powerful one. You probably won't sleep well afterwards. But you will far better understand what's at stake when Vladimir Putin orders Russia's military to rehearse the use of so-called tactical nuclear weapons in combat, as he did in May this year. Or if a newly-elected Donald Trump repeats the threat he made against North Korea in 2017 of 'fire and fury like the world has never seen'.

Turning away from the truth of nuclear weapons, whilst certainly a lot more comfortable, won't make us any safer. To quote the eminent 20th century American historian Henry Steele Commager:

“The greatest danger that threatens us is neither heterodox thought nor orthodox thought, but the absence of thought.”

Thanks for reading this very long post - there’s just SO much to say about this film! I’d love to keep the conversation going so if you watched the BBC re-run a couple of weeks ago (or whenever else you may have watched it) and have thoughts to share, do send them my way, via email or in the comments.

And I’d also love to get your recommendations for other atomic films that have made an impression on you for future Substack posts, watch parties etc. And look out for a bit more Threads-related goodness coming your way soon…

Watch my film on Netflix (in Europe) or Vimeo (everywhere else) - or see trailer, reviews & bonus content HERE

Find me on X /Twitter & at LinkedIn

Life stories website – coming soon...

You can check out the full listings for that evening here https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/schedules/service_bbc_two_england/1984-09-23

Knowing that director Mick Jackson and his wife were themselves expecting a baby during the making of Threads adds an even greater sting to what is certainly one of the most shocking and memorable scenes in the film

By way of comparison, Christopher Nolan's 2023 Oppenheimer had a budget of $100 million or around £70 million – so around 60 times higher

It’s also been released a couple of times on DVD and on remastered Blu-ray in 2017, with a new 4K Ultra-HD version set to be released next year

As well as Threads other titles from this period include the Raymond Briggs animated film When the Wind Blows from 1986 and in the US, The Day After and Testament, both from 1983

An almost excellent post. I say "almost" because i think there are other potential triggers for a nuclear war than the ones you mention. I didn't see Threads, but thanks to your post I've added it to my watchlist on the BBC iPlayer at some point.

Did you ever see The War Game by Peter Watkins? It was made in the 1960s and was terrifying, again all based on the known facts about the effects of atom bombs. The BBC banned it for five years. It's available on Amazon Prime for a fee.

I'm just old enough to recall the Cuban missile crisis, and that was pretty worrying.

During the 1970s and1980s there was a lot of scare stories about the impending aramgeddon, and there was a ludicrous public information film called Protect and Survive: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7yrv505R-0U Perhaps it did some good by making people feel less hopeless about their survival chances.

I was about to move to Sheffield, the week after watching this. I still have my diary for that year, and just wrote "evil stuff" - you can see the contextual roots of anarcho-punk and goth in this program and its overwhelming climate of fear and the pure banality of superpowers. There's a bit of urban mythology about the chalk outlines of the vaporised bodies being a little more permanent than agreed