The Atom & Us: Angenita Teekens

"Society needs better discussions, education and honesty around how, and for what reason, we use our nuclear understanding. Art plays a role."

Thanks for reading ‘The Atom & Us’, a series of interviews in which I’m spotlighting the work and insights of some of the incredibly interesting individuals I've been privileged to get to know through making & distributing my own nuclear history film, 'The Atom: A Love Affair' - from scholars and artists, to industry professionals, campaigners and more.

Together, I hope their shared ideas & experiences of the atomic age will help us all deepen our understanding of one of the most vital & urgent - yet in my view also one of the least well-discussed & understood - topics of our 21st century world.

Hi gang and welcome back to my 'atomic parlour', for another absorbing nuclear culture encounter.

It comes at the end of a week of frankly dizzying nuclear headlines - Donald Trump talking up the dangers of 'monster' nuclear weapons that could cause the 'end of the world'; European leaders discussing the need for a nuclear deterrent fully independent of the US; Russian and Chinese talks about Iran's nuclear programme; another nuclear fusion record achieved; and major tech giants including Google, Meta & Amazon signing onto a pledge to triple global nuclear power capacity by 2050.

Not to mention the anniversary of the nuclear disaster at Fukushima, which, hard as it may be to believe, happened a whole 14 years ago this week (here’s a little snippet from my film to mark the occasion).

I'm not sure I can remember a time in which nuclear issues were as front and centre in the news as they seem to be right now, at least not in the almost 20 years since I started paying proper attention to them.

And against such a backdrop, the need to take a moment, to step outside the rush of constantly updating events and think about things in a spacious, calm and considered manner, feels greater than ever.

I hope these pieces allow you a moment to do just that.

Just a quick recap before we get going. Each post will see my guest respond to the same set of questions, allowing them to share and reflect upon their experiences of, and ideas about, various aspects of our atomic world, as informed by their own individual connections to them.

Then I'll jump back in at the end with some of my thoughts - and of course you, the reader, are warmly invited to join the conversation too, either by replying if you're reading in email, or by hitting the comment button in the app. You can download that here if you'd like to check out the full-fat Substack experience for yourself (it tastes delicious I promise 😄):

And so on to business. It's my great pleasure to introduce my interviewee today:

Angenita Teekens

Angenita is a Dutch-born, British-based, collaborative and community artist and teacher, with a Master’s degree in Sculptural Practice from the University of Essex. She works in short films and photography, multi-media drawing, textiles and wild clay and her process often involves working in a specific landscape, incorporating archives, history and natural history, with a particular focus on the energy transition.

We met through the Art in the Nuclear Age book group, which I've talked about in this newsletter previously and which she also mentions in her interview (and small side note: AiNA are going to be doing a special edition of the book group soon discussing my film, which is super exciting for me and which I will of course be loudly spreading the word about when the time comes!)

I'm thrilled to be featuring her here as the first artist in this series - the first of many, I hope. It's no exaggeration to say that some of the most suggestive and stimulating work on nuclear issues I've come across over the past few years has come from artists so I'm very keen to feature more of that work in future posts.

But before then, here’s my interview with Angenita for you to enjoy.

Who are you and what's your connection to 'the atom'?

I am Angenita Teekens, a visual artist working around, in and on the Blackwater estuary in Essex, in the south east of England.

Sailing out of Brightlingsea harbour, this is our view. A timeline of energy production and beliefs.

Bradwell A, a decommissioned nuclear power station stands on the right, a beacon for sailors and visible from almost anywhere along and on the river / On the left, St. Peter-on-the-Wall, a 6th Century chapel built using the rubble from the Roman fort Ythancester / Left of the chapel, on shore wind generators / In between, behind the thicket, the off-grid Othona Community, where I lived for 5 years as the manager.

The year I left, 2002 , the power station was turned off and the humming stopped.

The river Blackwater, its course and culture, indefinitely changed with the arrival of the power station in 1957. I am fascinated by the shoreline, punctuated by the beliefs of religion, a better society, hopes and dreams, whether paradise or a booming economy with cheap electricity for all.

As an artist I look at this optically, what do I see and, critically, what does it all mean.

Through documentation and researching archival material and actively connecting with the land and sea scape I try and make sense of it.

Tell me about your early memories, thoughts & feelings about nuclear - can you remember when & how you first encountered anything atomic (something you read or saw on the news, or at school maybe, or encountered some other way?)

I have 2 early memories:

1) I did chemistry in secondary school. The teacher explained the vibration of atoms. I was absolutely fascinated by the idea that everything vibrates, that all living and non-living entities have this in common, that this is how we are connected to the universe.

and 2) I grew up in the Netherlands and was a teenager/ young adult during the time (1981–83) of mass demonstrations against the placement of US neutron bombs on Dutch soil.

An American historian Walter Laquer called this pacifist anti- American movement Hollanditis. The demonstrations were discussed at home and my parents who were children during WW2 were convinced that the threat of nuclear war kept the peace.

I did not agree.

Two of my father’s sisters moved as young women to America after World War 2 to escape the war-ravaged Netherlands and start a new life. Contrary to my Ronald Reagan-supporting, American aunt, I thought Hollanditis was a disease worth having. The thought of nuclear war filled me with dread and anger. I was 19, studying art and wanted to live and have a life.

When did you first become actively engaged in working in/thinking about nuclear and what did that look like for you?

I lived at The Othona Community for 5 years managing the site and programme. Bradwell A was a neighbour, about a mile away. When school groups had a residency at the centre, they visited Bradwell A. I went with the groups and visited the power station and gift shop many times.

Under a layer of dust, iodine tablets were stacked in my office drawer, just in case.

In April 2002, just a month after the humming stopped and the reactors shut down, I attended as a local business representative an ‘information breakfast’ about the future of the Bradwell A site. We were given information about decommissioning; we were informed that there were at that time no plans for a new nuclear power station and that the site was not going to be used for storage of nuclear waste.

Being 8 months pregnant at the time, I was relieved to hear this.

After leaving my job at the Othona Centre, I picked up my freelance artist career and started to think about the nuclear from a cultural point of view. Meeting Warren Harper and James Ravinet at the Othona Centre helped me to get connected with the Nuclear Culture Research Group and Art in The Nuclear Age. These networks and a successful DYCP application1 set me off on my current trajectory.

Is there an event or experience from your personal involvement with nuclear that particularly stands out in your memory and why?

In 1986 we were not allowed to eat spinach as it was contaminated by the outfall of atomic particles from the Chernobyl accident.

A close family member was living in Poland at the time - we were worried about his health and situation as fall out in Poland occurred soon after the accident. We wondered if he would receive the right information. Communications were not easy between the East and West block, often the calls were tapped and cut off. It took a while before we could talk to him.

I moved to London in 1989 through a teacher’s scheme. Due to a shortage of teachers we ( graduates fresh from teaching training college) were recruited by the British Government to come and work in London and given a council flat; mine was next to the railway in Barking.

Once a week a night train passed, a heavy diesel, noisy, shaking the building, waking me up. I found out that this was the train from Southminster (close to Bradwell A) to Sellafield carrying spent nuclear fuel.

Why do you personally find it a compelling topic?

The nuclear penetrates everything we do. From the building blocks of all living and non-living bodies, the vibrating atom, to the innate desire of human society to control, change and experiment.

Nuclear material and processes test the limit of human knowledge and choices. To control these very small elements, bend them to our will and desires, takes incredible specialised knowledge. The excitement about that knowledge, when talking to the nuclear scientists, is infectious.

This highly specialised knowledge and experimentation is hard to be guided by democratic systems. What does the average constituent know about the nuclear ?

Still, their lives will be touch by it, from x rays and fallout from nuclear accidents, to the possibility of a nuclear war. So, we all should have an opinion about it really.

It never worried me to live so close to a nuclear power plant. The Dengie coast is a beautiful area with a darkness and silence seldom experienced in the south of the UK.

I always think it is amusing that I lived off grid with a young family, right next to a nuclear plant. It proved to me without any doubt that we can live, domestically at least, without the need for nuclear energy.

Why do you think it has always been such a polarising issue and do you have any thoughts on if/how the discourse can be expanded to move beyond a simplistic pro- or anti- binary opposition?

Living in a democracy, we have to choose when visiting the ballot box. Do we vote for /against nuclear armament ? For, or against nuclear energy?

That creates polarisation. It also carries a realism - you either build that nuclear power station or you don’t.

In term of consideration? The issues are complex, planetary, morally challenging. Society needs better discussions, education and honesty around how, and for what reason, we use our nuclear understanding. Art plays a role. I believe this can lead to less simplicity and ultimately better decisions.

What's the most interesting or important thing about nuclear you'd want to tell people that they might not already know?

Oops that is a hard one. How about this:

Carbon 14 increased so dramatically in the atmosphere during the bomb testing period in the 50s, it was re-named bomb carbon -14. This isotope ended up everywhere, also in humans. Analysing bomb carbon-14 in human remains, bones, teeth and hair can help to solve crimes2.

Someone out there who wants to write a crime novel?

Do you have a favourite bit of atomic culture (song, film, book, video game – anything else!) you'd like to share?

I have two:

1) De Bom, a ska-pop protest song by 1980s Dutch band Doe Maar.3

The youth of the 80s in The Netherlands was characterised by ‘doem denken’ (doom thinking) - we were the ‘doem denkers’. De Bom, was a musical hit by a popular boy band, a tragic love song, just a perfect bit of culture translating how we felt about life and our future. Excellent in the student discos, especially at the end of the song, when we all fell over pretending to be hit by De Bom.

2) In 2021 I received a DYCP grant from the Arts Council for my research project : ‘Swimming the Nuclear”.

This gave me the opportunity to enter the National Archives and research Bradwell A. I found the original technical drawings of the inlet and outlet constructions of the cooling water. I was moved by this drawing. I have a weak spot for technical drawings, this one came in an archival box, smelling of parchment, the paper was stiff and resisted being unfolded.

I discovered by association a commonality between the famous Mersea Oyster and this drawing. My blog tells more: Swimming the Nuclear: Inlet and Outlet

What do you think I should ask other people about their experiences and thoughts around nuclear?

What their (nuclear) networks are.

Huge thanks to Angenita for her insights and especially for giving us a glimpse into her artistic exploration of nuclear culture in and around Bradwell and the Essex coast.

By one of those quirks of fate, Bradwell ended up being the most featured British nuclear site in my film after Windscale/Sellafield, so it's a place I too feel quite connected to.

I spent a memorable day filming in a pub nearby with a group of retired Bradwell employees who'd worked there in the early years after it opened in 1962. And I discovered that one of my interviewees, British nuclear policy academic Professor Steve Thomas, and a colleague I worked with at an early stage of post-production, the award-winning film editor Claire Ferguson, had both grown up in the area.

I found some wonderful archive footage of the plant during construction which I was able to use in the film:

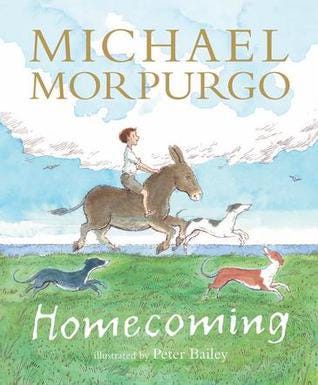

And Claire also shared with me the beautiful book Homecoming, by legendary children's author Michael Morpurgo, which tells the story of the plant's inception on the Essex marshes through a very different lens and also features St Peter’s chapel, as seen in Angenita’s photo above4.

The connection with water which Angenita's work touches on in such a tender and personal way, through swimming, is one that I don't think is always much acknowledged in mainstream discourse around nuclear energy (the row around the proposed 'fish disco' deterrent at the under-construction Hinkley C plant being a recent notable exception).

But nuclear power plants do need very large quantities of water (hence why they’re typically built on the coast or by rivers) and there are implications around this for society to consider. I very much agree with Angenita that art can pose questions and invite consideration in a different way that can hopefully help people grapple with these implications in all their human and social complexity.

Finally, I was really interested to hear a little about her experience as a teenager in Holland in the 1980s. It wasn't deliberate but I realised that three of the four posts I've published in this series now have been with people with links to countries other than my own (as well as Angenita and the Netherlands, there was Min-Kyoo Kim and South Korea and Cornelius Holtorf and Germany/Sweden).

I think these international perspectives are especially helpful in reminding us how contingent upon a particular time and place our own deep feelings may be, even if we don't always realise it.

Plus, that De Bom song is an absolute banger, I think we can all agree (I defy you not to get the chorus stuck in your head after listening to it!)

To close, I'd love to invite you to answer Angenita's last question - what are your nuclear networks? Do let me know (perhaps this Substack is one of them!)

Watch my film on Netflix & Disney+ (UK/Europe only) or Vimeo-on-demand - or see trailer, reviews & bonus content HERE

Find me on Bluesky & at LinkedIn

Thank you for being here, please ❤️ (below) or restack if you enjoyed this piece, it really does helps others find it.

Developing Your Creative Practice - the main Arts Council grant funding directed towards individual cultural and creative practitioners in England

BBC Future have a good article going into more depth about this “bomb spike” if you’re interested in learning more.

You can probably pick up the gist of the main line in the chorus even if you don’t speak Dutch (voordat de bom valt = before the bomb falls), but if you want to see the full lyrics translated into English, you can do that here.

I plan to do a video book report on this book at some point - the illustrations by Peter Bailey are worth the price of admission alone

An interesting interview about a place close to my heart. As a young child, my father used to take my siblings and I swimming in front of Bradwell A, as he felt the water was a little warmer there! My mother was somewhat concerned for our welfare, dad just shrugged it off. I’m happy to report that some 50 plus years later, we kids don’t seem to have suffered from the experience, though this has not stopped me from being heavily involved in campaigning against a Bradwell B.

St Peter’s chapel remains an iconic building within the liminal landscape and one worth preserving from the devastation of any future nuclear infrastructure. As an artist, the local landscape provides much inspiration, though the view of now clad reactors from where I’m currently sitting at my desk, not so much!