...in the A-Z of my favourite documentary films

I’m creating a library of posts on the documentary films that have meant the most to me - you can read more about the whole project, the criteria for inclusion and see the master list here:

And if you like it, why not subscribe to receive all the new posts in the series as I add them!

Note: This piece was first published on The Oscar Project as part of the Sept 2024 Movie Challenge by - big thanks to Jonathan for inviting me to collaborate and do check out his Substack where he’s doing all kinds of cool things with movies new & old 😃

When Jonathan told me he was planning to include Koyaanisqatsi in his September movie challenge and asked if I'd like to collaborate on a post about it – since it also features on my own A-Z list of favourite documentary films – of course, I jumped at the chance. Whilst some purists might baulk at calling it a documentary, for me it definitely falls under any expansive definition of creative non-fiction filmmaking. In fact, it's one of the very best examples I can think of.

This is a film that takes three of the essential ingredients of cinema – image, sound and feeling – and then simply strips everything else away. With no plot and no characters, this avant-garde, experimental approach provides an unforgettable viewing experience, one felt in the senses, in the body and the gut, far more than in the mind.

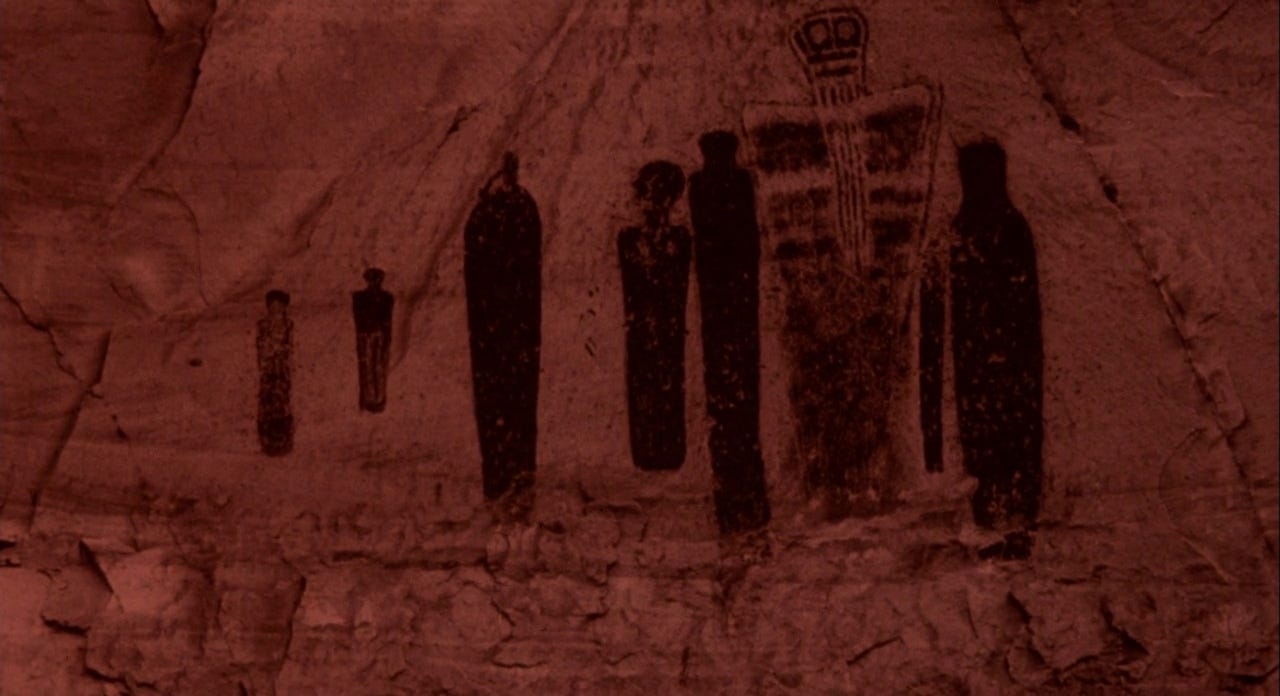

In some ways, it almost feels like watching a concert film, except that the stars of the performance are nature and civilisation themselves. There are famously extended timelapse scenes where the sped up motion, edited in time with Philip Glass's pulsating, hypnotic score, makes it feel like we're watching formally choreographed dance sequences out of everything from the shadows of clouds passing across giant rock formations and commuters streaming up escalators, to factory production lines, and mailroom sorting machines.

Director Godfrey Reggio takes viewers from placid desert landscapes to urban sprawls, all without direct commentary other than the visuals and music.

These sequences are almost exhilarating to watch. But they're also strangely unsettling – and re-watching the film for this post, it was this openness, like a literary text that resists straightforward understanding, that especially stood out to me.

Beyond the high-level themes of planetary balance and the complex interplay between the natural world and the technological one humans have built within and upon it, director Godfrey Reggio never explicitly tells you what to think or feel. As a viewer you're not shepherded to respond in any particular way but rather, to bring your own reaction, your own interpretation to the table.

And so to finish my contribution to appreciating this incredible piece of work, I'd like to highlight a brief section from about half way through the film, which I think shows this especially well.

It begins with a super sped up timelapse sequence of a crowd queueing in what looks like a train station, followed by a series of slowed down shots of pedestrians walking along busy city streets. These scenes are so familiar – I've shot umpteen versions of them across my entire career for documentaries I've worked on. They're so generic, at this point they border on the cliched. Yet in slowing them way down, they are defamiliarised and leap off the screen in a completely fresh way, forcing you to look so much more closely, both at the surroundings and at the faces.

And yet more faces follow in the final part of the clip, with a series of portrait shots of people looking straight down the lens. These shots feel almost confronting in their total lack of context and explanation. The expressions on the faces feel inscrutable, almost uncanny. What are they thinking, what are they trying to tell us?

There is of course no answer, or at least no 'right answer'. And that I think is true of the movie as a whole. It means what you want it to mean (and that may or may not be something different here in 2024 than it would have been back in 1982). But whatever it means to you, this is a movie that once seen, I'm sure you'll never forget.

Koyaanisqatsi is widely available to view online. It’s also been released in various DVD & Blu-ray versions, most recently in 2012 by the Criterion Collection as part of a 3 disc box set containing two subsequent companion films also made by Reggio (and scored by Philip Glass), Powaqqatsi (1988) and Nagoyqatsi (2002).

If you’ve seen it, I’d love to know your thoughts - comments open as always 😃

Watch my film on Netflix (in Europe) or Vimeo (everywhere else) - or see trailer, reviews & bonus content HERE

Life stories website – coming soon...